Mikhail Gorbachev had been the leader of the Soviet Union for just 13 days when he was suddenly faced with an international crisis.

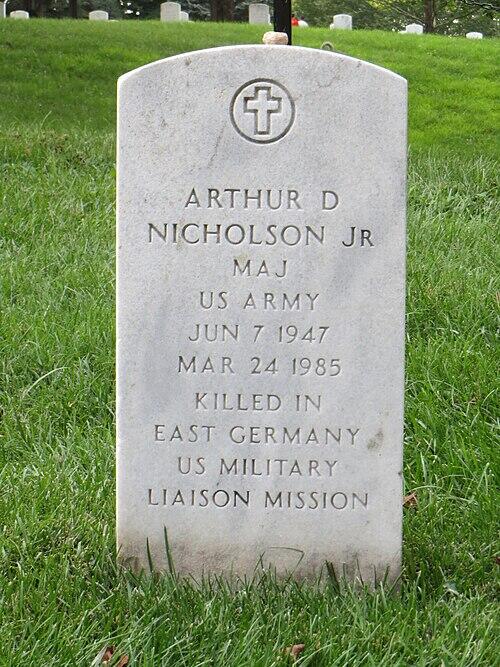

On March 24, 1985, a Soviet sentry shot and killed U.S. Army Maj. Arthur D. “Nick” Nicholson Jr. near a tank storage building in Ludwigslust, East Germany. Nicholson was unarmed and in his uniform. His vehicle carried clearly marked plates identifying him as a member of the U.S. Military Liaison Mission, an organization authorized by both governments to operate in the other’s territory.

The U.S. Department of War officially considers his death a murder. It also considers Nicholson the final American death of the Cold War.

Arthur D. Nicholson

Nicholson grew up in Redding, Connecticut, in a military household. His father was a retired Navy commander. After graduating from Joel Barlow High School in 1965, he attended Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, and entered the Army in 1970.

The service sent him abroad almost immediately. He first worked an intelligence posting with a missile battalion in South Korea through 1973 and 1974. He then transferred to West Germany, where he spent the next five years embedded with MI units in Frankfurt and Munich. The assignment cemented his interest on Soviet affairs. He became fluent in Russian and built a deep understanding of how the Red Army trained, organized and deployed its forces.

That expertise led Nicholson toward an increasingly specialized track. He completed graduate work in Soviet and East European studies at the Naval Postgraduate School and spent two years studying the Russian language at the Defense Language Institute. Additional training at the Army’s Russian Institute in the Bavarian Alps made him uniquely qualified for front-line intelligence work.

By 1982, the Army placed him in one of its most unusual and dangerous billets. He was assigned to the U.S. Military Liaison Mission, headquartered in Potsdam, East Germany.

Intelligence Work

The USMLM traced its origins to the final months of World War II. When the Allies divided Germany into occupation zones, they needed a way to communicate across them. In April 1947, Lt. Gen. Clarence Huebner and Soviet Colonel-General Mikhail Malinin signed an agreement allowing each side to station small military teams in the other’s territory.

The original purpose was coordination and monitoring of German disarmament. But as the Cold War set in, the missions became a way for both sides to collect intelligence. The Americans, British and French sent teams into East Germany. The Soviets operated reciprocal units in West Germany. Everyone understood the arrangement. Both sides found it a convenient way to monitor each other’s forces without triggering a confrontation.

The USMLM was authorized 14 accredited officers who could travel through East Germany observing and documenting Soviet military exercises, equipment and facilities. They carried cameras and binoculars instead of weapons. Their vehicles bore distinctive plates that identified them as liaison mission personnel.

“He wanted to be out there, and he needed to be out there, close to what he considered the cutting edge,” Col. Roland LaJoie, Nicholson’s commanding officer, later said.

The work produced positive results. USMLM personnel provided Washington with ground-level assessments of Soviet military strength that no satellite image could match. Their patrols identified previously unknown weapons platforms before they appeared anywhere else in American intelligence reporting. They also gathered information on troop morale, readiness and manning levels that painted a far more nuanced picture of Soviet capability than top-level estimates suggested.

The missions were also dangerous. Nicholson himself had once been part of a team that managed to get inside a Soviet tank and photograph its entire interior. Soviet and East German forces regularly harassed and confronted USMLM patrols. Then on March 24, Nicholson was ordered across the border again.

“It should have been a milk run,” LaJoie said.

The Shooting

That Sunday morning, Nicholson and his driver, Staff Sgt. Jessie Schatz, headed into East Germany in their marked vehicle. They followed a convoy of Soviet tanks returning from target practice. At some point, they broke off and approached a tank storage shed used by an independent tank regiment of the 2nd Guards Tank Army near Ludwigslust, roughly 100 miles northwest of Berlin.

Nicholson got out to photograph the building. He carried a 35mm camera and binoculars. No weapon. Schatz stayed with the vehicle and watched for Soviet personnel. Neither man detected Soviet Sgt. Aleksandr Ryabtsev, who had slipped out of the woods behind them.

Ryabtsev’s first round flew past Schatz’s head. Nicholson turned toward the vehicle. A second shot hit him in the chest.

“Jessie, I’ve been shot!” Nicholson called out as he collapsed.

Schatz grabbed his first aid kit and held up the Red Cross emblem to signal peaceful intent. Ryabtsev leveled his AK-47 at Schatz and pinned him inside the vehicle. For over an hour, Nicholson lay on the ground. Nobody touched him or checked his pulse.

The Soviets later claimed he died instantly. An American autopsy confirmed that Nicholson bled to death on the ground while Soviet soldiers stood nearby and did nothing.

Confrontation at the Scene

LaJoie received an urgent call from his headquarters that afternoon. The Soviets were demanding to see him. He grabbed his deputy, Lt. Col. Lawrence Kelley, and a driver and raced toward Ludwigslust, more than two hours from Berlin.

Soviet troops met them and escorted them to the site. No one told them what had happened. When they arrived, LaJoie saw a ring of military trucks with their headlights trained on the area.

“I thought, ‘This is bad,'” he recalled.

They found Schatz sitting in his vehicle. They asked where Nicholson was. The answer confirmed their worst fears.

A Soviet three-star general confronted LaJoie and tried to seize control of the situation. He demanded the American vehicle, Nicholson’s body for autopsy and the right to interrogate Schatz.

LaJoie refused on every point. After more than two hours of tense negotiation in Russian, he got the general to back down. Around midnight, LaJoie took Schatz and both vehicles back to West Berlin, leaving Kelley behind to watch over Nicholson’s body.

“I was the last of us to see Nick alive and the first to see him dead,” LaJoie said at the funeral.

A Diplomatic Crisis

The shooting sent shockwaves through Washington and Moscow. It became Gorbachev’s first foreign policy crisis as Soviet leader, threatening to undo any prospect of improved relations with the West.

U.S. Army investigators concluded that Nicholson’s killing was “officially condoned, if not directly ordered” by Soviet leadership. The State Department declared the Soviet account of the incident “a distortion of the facts.” The Soviets claimed Ryabtsev had challenged an unknown intruder who refused to comply with warnings. Schatz spoke fluent German and heard no verbal warning of any kind before the shots.

In response, Washington expelled a Soviet diplomat. Plans for the U.S. and Soviet Union to mark the 40th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day together were scrapped. Secretary of State George Shultz sat down with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to hammer out safeguards against future confrontations.

Subsequent negotiations produced a Soviet directive that barred the use of weapons or physical force against allied liaison personnel. That pledge proved ineffective. Two years later, in 1987, Soviet troops opened fire on another USMLM patrol and wounded an American serviceman.

Coming Home

After a standoff over whether the Soviets could perform an autopsy, Gen. Glenn K. Otis demanded the body be handed over. The transfer took place at the Glienicke Bridge, the same Cold War landmark where the superpowers had swapped captured spies.

His flag-draped casket was then flown to Rhein-Main Air Base in Frankfurt on March 29, 1985. His wife, Karyn, and their 9-year-old daughter, Jennifer, stood on the tarmac as a military band played. Jennifer clutched a doll in one hand.

At Andrews Air Force Base the next day, Vice President George H.W. Bush met the family. He called Nicholson “an outstanding officer murdered in the line of duty.” He warned the Soviets that “this sort of brutal international behavior jeopardizes directly the improvements in relations.”

Nicholson was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on March 31 in Section 7A, near his father. All 13 of his USMLM teammates attended. Several hundred mourners gathered at Fort Myer’s Memorial Chapel as LaJoie delivered a eulogy.

“It was not a battle, it was not a fair fight,” LaJoie said. “He was unarmed, in uniform, in broad daylight.”

Nicholson’s widow spoke of her husband’s death.

“Nick did not want to die, and we did not want to lose him,” she said. “But I know that he would lay down his life again for America.”

The Last American Killed in the Cold War

President Ronald Reagan approved Nicholson’s posthumous promotion to lieutenant colonel. He also received the Legion of Merit and the Purple Heart.

Three years passed before the Soviets offered any real acknowledgment. At a 1988 summit in Moscow, Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov told his American counterpart, Frank Carlucci, that the Soviet government was sorry for what happened to Nicholson.

In 1991, the Military Intelligence community added him to its Hall of Fame. By then, the Cold War he had spent his career monitoring was already over. Germany had reunified the previous October. The Soviet Union itself would cease to exist before the year was over.

At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, the Army’s intelligence training center, a building called Nicholson Hall keeps his name in front of every new generation of MI soldiers. A memorial stone stands near the site of his death in Ludwigslust, dedicated in 2005 with Karyn and LaJoie in attendance.

The USMLM shut down on Oct. 2, 1990, one day before East and West Germany merged back into a single nation. Its mission was complete. The wall had come down less than five years after Nicholson’s death.

LaJoie rose to major general before retiring in 1994. In 1988, the Reagan administration tapped him to build the On-Site Inspection Agency, which sent American teams into Soviet territory to verify compliance with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. His inspectors confirmed the destruction of 1,800 Soviet missiles at 133 sites. Some of the officers he recruited for those inspection teams were veterans of the same USMLM patrols that had once put them in the crosshairs of Soviet sentries.

LaJoie died in October 2023 at age 87. He asked to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, close to Nicholson.

“He not only passed the tests, he set the standards,” LaJoie said of the officer.

According to the Department of War, Nicholson was the last official American service member killed in the line of duty during the Cold War. However, several more were wounded or injured in the final years before the Iron Curtain finally collapsed.

Read the full article here

40 Comments

Nice to see insider buying—usually a good signal in this space.

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Interesting update on The Last American Killed During the Cold War Was an Army Major Shot by a Soviet Soldier. Curious how the grades will trend next quarter.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Production mix shifting toward USA might help margins if metals stay firm.

Silver leverage is strong here; beta cuts both ways though.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

The cost guidance is better than expected. If they deliver, the stock could rerate.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Uranium names keep pushing higher—supply still tight into 2026.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

If AISC keeps dropping, this becomes investable for me.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

Exploration results look promising, but permitting will be the key risk.

I like the balance sheet here—less leverage than peers.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

The cost guidance is better than expected. If they deliver, the stock could rerate.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Interesting update on The Last American Killed During the Cold War Was an Army Major Shot by a Soviet Soldier. Curious how the grades will trend next quarter.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.

Good point. Watching costs and grades closely.